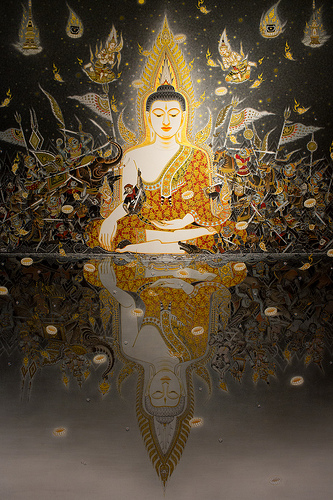

Wisdom Quarterly: The problem is tanha (craving, the cause of suffering, literally "thirst"). The solution is nirvana (extinguishing suffering, metaphorically "going out").

Wisdom Quarterly: The problem is tanha (craving, the cause of suffering, literally "thirst"). The solution is nirvana (extinguishing suffering, metaphorically "going out").Back in the days of the Buddha, nirvana (Pali, nibbana) had a verb of its own: nibbuti. It meant to "go out," like a flame.

Because fire was thought to be in a state of entrapment as it burned — both clinging to and trapped by the fuel on which it fed — its going out was seen as an unbinding. To go out was to be unbound. Sometimes another verb was used — parinibbuti — with the "pari-" meaning total or all-around, to indicate that the person unbound, unlike fire unbound, would never again be trapped.

Now that nirvana has become an English word, it should have its own English verb to convey the sense of "being unbound" as well. At present, we say that a person "reaches" nirvana or "enters" nirvana, implying that nibbana is a place where you can go.

This may seem like a word-chopper's problem. (What can a verb or two do to your practice?) But the idea of nirvana as a place has created severe misunderstandings in the past, and it could easily create misunderstandings now.

However, these philosophers misunderstood two important points about the Buddha's teachings. The first was that neither samsara nor nirvana is a place. Samsara is a process of creating places, even whole worlds (called becoming) and then wandering through them (called birth). Nirvana is the end of this process.

The second point is that nirvana, from the very beginning, was realized through unestablished consciousness — one that neither comes, nor goes, nor stays in place. There is no way that anything unestablished can get stuck anywhere at all, for it is not only non-localized but also undefined [and undefinable]. More>>